Unicode is harder than you think

23 Jul 2023Reading the excellent article by JeanHeyd Meneide on how broken string encoding in C/C++ is made me realise that Unicode is a topic that is often overlooked by a large number of developers. In my experience, there’s a lot of confusion and wrong expectations on what Unicode is, and what best practices to follow when dealing with strings that may contain characters outside of the ASCII range.

This article attempts to briefly summarise and clarify some of the most common misconceptions I’ve seen people struggle with, and some of the pitfalls that tend to recur in codebases that have to deal with non-ASCII text.

The convenience of ASCII

Text is usually represented and stored as a sequence of numerical values in binary form. Wherever its source is, to be represented in a way the user can understand it needs to be decoded from its binary representation, as specified by a given character encoding.

One such example of this is ASCII, the US-centric standard which has been for decades the de-facto way to represent characters and symbols in C and UNIX. ASCII is a 7-bit encoding, which means that it can represent up to 128 different characters. The first 32 characters are control characters, which are not printable, and the remaining 96 are printable characters, which include the 26 letters of the English alphabet, the 10 digits, and a few symbols:

Dec Hex Dec Hex Dec Hex Dec Hex Dec Hex Dec Hex Dec Hex Dec Hex

0 00 NUL 16 10 DLE 32 20 48 30 0 64 40 @ 80 50 P 96 60 ` 112 70 p

1 01 SOH 17 11 DC1 33 21 ! 49 31 1 65 41 A 81 51 Q 97 61 a 113 71 q

2 02 STX 18 12 DC2 34 22 " 50 32 2 66 42 B 82 52 R 98 62 b 114 72 r

3 03 ETX 19 13 DC3 35 23 # 51 33 3 67 43 C 83 53 S 99 63 c 115 73 s

4 04 EOT 20 14 DC4 36 24 $ 52 34 4 68 44 D 84 54 T 100 64 d 116 74 t

5 05 ENQ 21 15 NAK 37 25 % 53 35 5 69 45 E 85 55 U 101 65 e 117 75 u

6 06 ACK 22 16 SYN 38 26 & 54 36 6 70 46 F 86 56 V 102 66 f 118 76 v

7 07 BEL 23 17 ETB 39 27 ' 55 37 7 71 47 G 87 57 W 103 67 g 119 77 w

8 08 BS 24 18 CAN 40 28 ( 56 38 8 72 48 H 88 58 X 104 68 h 120 78 x

9 09 HT 25 19 EM 41 29 ) 57 39 9 73 49 I 89 59 Y 105 69 i 121 79 y

10 0A LF 26 1A SUB 42 2A * 58 3A : 74 4A J 90 5A Z 106 6A j 122 7A z

11 0B VT 27 1B ESC 43 2B + 59 3B ; 75 4B K 91 5B [ 107 6B k 123 7B {

12 0C FF 28 1C FS 44 2C , 60 3C < 76 4C L 92 5C \ 108 6C l 124 7C |

13 0D CR 29 1D GS 45 2D - 61 3D = 77 4D M 93 5D ] 109 6D m 125 7D }

14 0E SO 30 1E RS 46 2E . 62 3E > 78 4E N 94 5E ^ 110 6E n 126 7E ~

15 0F SI 31 1F US 47 2F / 63 3F ? 79 4F O 95 5F _ 111 6F o 127 7F DEL

This table defines a two-way transformation, in jargon a charset, which maps a certain sequence of bits (representing a number) to a given character, and vice versa. This can be easily seen by dumping some text as binary:

$ echo -n Cat! | xxd

00000000: 4361 7421 Cat!

The first column represents the binary representation of the input string “Cat!” in hexadecimal form. Each character is mapped into a single byte (represented here as two hexadecimal digits):

43is the hexadecimal representation of the ASCII characterC;61is the hexadecimal representation of the ASCII charactera;74is the hexadecimal representation of the ASCII charactert;21is the hexadecimal representation of the ASCII character!.

This simple set of characters was for decades considered more than enough by most of the English-speaking world, which was where the vast majority of computer early computer users and pioneers came from.

An added benefit of ASCII is that it is a fixed-width encoding: each character is always represented univocally by the same number of bits, that in turn always represent the same number.

This leads to some very convenient ergonomics when handling strings in C:

#include <ctype.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(const int argc, const char *argv[const]) {

// converts all arguments to uppercase

for (const char *const *arg = argv + 1; *arg; ++arg) {

// iterate over each character in the string, and print its uppercase

for (const char *it = *arg; *it; ++it) {

putchar(toupper(*it));

}

if (*(arg + 1)) {

putchar(' ');

}

}

if (argc > 1) {

putchar('\n');

}

return 0;

}

The example above assumes, like a large amount of code written in the last few decades, that the C basic type char represents a byte-sized ASCII character. This assumption minimises the mental and runtime overhead of handling text, as strings can be treated as arrays of characters belonging to a very minimal set. Because of this, ASCII strings can be iterated on, addressed individually and transformed or inspected using simple, cheap operations such as isalpha or toupper.

The world outside

However, as computers started to spread worldwide it became clear that it was necessary to devise character sets capable to represent all the characters required in a given locale. For instance, Spanish needs the letter ñ, Japan needs the ¥ symbol and support for Kana and Kanji, and so on.

All of this led to a massive proliferation of different character encodings, usually tied to a given language, area or locale. These varied from 8-bit encodings, which either extended ASCII by using its unused eighth bit (like ISO-8859-1) or completely replaced its character set (like KOI-7), to multi-byte encodings for Asian languages with thousands of characters like Shift-JIS and Big5.

This turned into a huge headache for both developers and users, as it was necessary to know (or deduce via hacky heuristics) which encoding was used for a given piece of text, for instance when receiving a file from the Internet, which was becoming more and more common thanks to email, IRC and the World Wide Web.

Most crucially, multibyte encodings (a necessity for Asian characters) meant that the assumption “one char = one byte” didn’t hold anymore, with the small side effect of breaking all code in existence at the time.

For a while, the most common solution was to use a single encoding for each language, and then hope for the best. This often led to garbled text (who hasn’t seen the infamous � character at least once), so much so that a specific term was coined to describe it - “mojibake”, from the Japanese “文字化け” (“character transformation”).

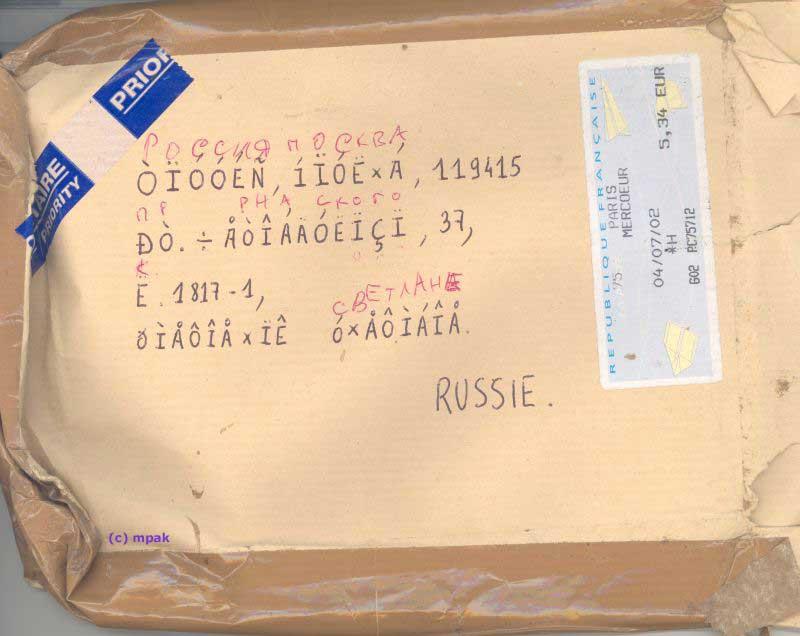

In general, for a long time using a non-English locale meant that you had to contend with broken third (often first) party software, patchy support for certain characters, and switching encodings on the fly depending on the context. The inconvenience was such that it was common for non-Latin Internet users to converse in their native languages with the Latin alphabet, using impromptu transliterations if necessary. A prime example of this was the Arabic chat alphabet widespread among Arabic-speaking netizens in the 90’s and 00’s 1.

Unicode

It was clear to most people back then that the situation as it was untenable, so much so that as early as the late ’80s people started proposing a universal character encoding capable to cover all modern scripts and symbols in use.

This led to the creation of Unicode, whose first version was standardised in 1991 after a few years of joint development led by Xerox and Apple (among others). Unicode main design goal was, and still is, to define a universal character set capable to represent all the aforementioned characters, alongside a character encoding capable of uniformly representing them all.

In Unicode, every character, or more properly code point, is represented by a unique number, belonging to a specific Unicode block. Crucially, the first block of Unicode (“Basic Latin”) corresponds point per point to ASCII, so that all ASCII characters correspond to equivalent Unicode codepoints.

Code points are usually represented with the syntax U+XXXX, where XXXX is the hexadecimal representation of the code point. For instance, the code point for the A character is U+0041, while the code point for the ñ character is U+00F1.

Unicode 1.0 covered 26 scripts and 7,161 characters, covering most of the world’s languages and lots of commonplace symbols and glyphs.

UCS-2, or “how Unicode made everything worse”

Alongside the first Unicode specification, which defined the character set, two2 new character encodings, called UCS-2 and UCS-4 (which came a bit later), were also introduced. UCS-2 was the original Unicode encoding, and it’s an extension of ASCII to 16 bits, representing what Unicode called the Basic Multilingual Plane (“BMP”); UCS-4 is the same but with 32-bit values. Both were fixed-width encodings, using multiple bytes to represent each single character in a string.

In particular, UCS-2’s maximum range of 65,536 possible values was good enough to cover the entire Unicode 1.0 set of characters. The storage savings compared with UCS-4 were quite enticing, also - while ’90s machines weren’t as constrained as the ones that came before, representing basic Latin characters with 4 bytes was still seen as an egregious waste.3

Thus, 16 bits quickly became the standard size for the wchar_t type recently added by the C89 standard to support wide characters for encodings like Shift-JIS. Sure, switching from char to wchar_t required developers to rewrite all code to use wide characters and wide functions, but a bit of sed was a small price to pay for the ability to resolve internationalization, right?

The C library had also introduced, alongside the new wide char type, a set of functions and types to handle wchar_t, wide strings and (poorly designed) functions locale support, including support for multibyte encodings. Some vendors, like Microsoft, even devised tricks to make it possible to optionally switch from legacy 8-bit codepages to UCS-2 by using ad-hoc types like TCHAR and LPTSTR in place of specific character types.

All of that said, the code snippet above could be rewritten on Win32 as the following:

#include <ctype.h>

#include <tchar.h>

#if !defined(_UNICODE) && !defined(UNICODE)

# include <stdio.h>

#endif

int _tmain(const int argc, const TCHAR *argv[const]) {

// converts all arguments to uppercase

for (const TCHAR *const *arg = argv + 1; *arg; ++arg) {

// iterate over each character in the string, and print its uppercase

for (const TCHAR *it = *arg; *it; ++it) {

_puttchar(_totupper(*it));

}

if (*(arg + 1)) {

_puttchar(_T(' '));

}

}

_puttchar(_T('\n'));

return 0;

}

Neat, right? This was indeed considered so convenient that developers jumped on the UCS-2 bandwagon in droves, finally glad the encoding mess was over.

16-bit Unicode was indeed a huge success, as attested by the number of applications and libraries that adopted it during the ’90s:

- Windows NT, 2000 and XP used UCS-2 as their internal character encoding, and exposed it to developers via the Win32 API;

- Apple’s Cocoa, too, used UCS-2 as its internal character encoding for

NSStringandunichar; - Sun’s Java used UCS-2 as its internal character encoding for all strings, even going as far as to define its String type as an array of 16-bit characters;

- Javascript, too, didn’t want to be left behind, and basically defined its String type the same way Java did;

- Qt, the popular C++ GUI framework, used UCS-2 as its internal character encoding, and exposed it to developers via the QString class;

- Unreal Engine just copied the WinAPI approach and used UCS-2 as its internal character encoding 4

and many more. Every once in a while, I still find out that some piece of code I frequently use is still using UCS-2 (or UTF-16, see later) internally. In general, every time you read something along the lines of “Unicode support” without any reference to UTF, there’s an almost 100% chance that it actually means “UCS-2”, or some borked variant of it.

Combining characters

Unicode supported since its first release the concept of combining characters (later better defined as grapheme clusters), which are clusters of characters meant to be combined with other characters in order to form a single unit by text processing tools.

In Unicode jargon, these are called composite sequences and were designed to allow Unicode to represent scripts like Arabic, which uses a lot of diacritics and other combining characters, without having to define a separate code point for each possible combination.

This could have been in principle a neat idea - grapheme clusters allow Unicode to save a massive amount of code points from being pointlessly wasted for easily combinable characters (just think about South Asian languages or Hangul). The real issue was that the Consortium, anxious to help with the transition to Unicode, did not want to drop support for dedicated codepoints for “preassembled” characters such as è and ñ, which were historically supported by the various extended ASCII encodings.

This led to Unicode supporting precomposed characters, which are codepoints that stand for a glyph that also be represented using a grapheme cluster. An example of this is the Extended Latin characters with accents or diacritics, which can all be represented by combining the base Latin character with the corresponding modifier, or by using a single code point.

For instance, let’s try testing out a few things with Python’s unicodedata and two seemingly identical strings, “caña” and “caña” (notice how they look the same):

>>> import unicodedata

>>> a, b = "caña", "caña"

>>> a == b

False

Uh?

>>> a, b

('caña', 'caña')

>>> len(a), len(b)

(4, 5)

The two strings are visually identical - they are rendered the same by our Unicode-enabled terminal - and yet, they do not evaluate as equal, and the len() function returns different lengths. This is because the ñ in the second string is a grapheme cluster composed of the U+006E LATIN SMALL LETTER N and U+0303 COMBINING TILDE character, combined by terminal into a single character.

>>> list(a), list(b)

(['c', 'a', 'ñ', 'a'], ['c', 'a', 'n', '̃', 'a'])

>>> [unicodedata.name(c) for c in a]

['LATIN SMALL LETTER C', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER A', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER N WITH TILDE', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER A']

>>> [unicodedata.name(c) for c in b]

['LATIN SMALL LETTER C', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER A', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER N', 'COMBINING TILDE', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER A']

This is obviously a big departure from the “strings are just arrays of characters” model the average developer is used to:

- Trivial comparisons like

a == borstrcmp(a, b)are no longer trivial. A Unicode-aware algorithm must to be implemented, in order to actually compare the strings as they are rendered or printed; - Random access to characters is no longer safe, because a single glyph can span over multiple code points, and thus over multiple array elements;

”640k 16 bits ought to be enough for everyone”

Anyone with any degree of familiarity with Asian languages will have noticed that 7,161 characters are way too small a number to include the tens of thousands of Chinese characters in existence. This is without counting minor and historical scripts, and the thousands of symbols and glyphs used in mathematics, music, and other fields.

In the years following 1991, the Unicode character set was thus expanded with tens of thousands of new characters, and it become quickly apparent that UCS-2 was soon going to run out of 16-bit code points.5

To circumvent this issue, the Unicode Consortium decided to expand the character set from 16 to 21 bits. This was a huge breaking change that basically meant obsoleting UCS-2 (and thus breaking most software designed in the ’90s), just a few years after its introduction and widespread adoption.

While UCS-2 was still capable of representing anything inside the BMP, it became clear a new encoding was needed to support the growing set of characters in the UCS.

UTF

The acronym “UTF” stands for “Unicode Transformation Format”, and represents a family of variable-width encodings capable of representing the whole Unicode character set, up to its hypothetical supported potential 2²¹ characters. Compared to UCS, UTF encodings specify how a given stream of bytes can be converted into a sequence of Unicode code points, and vice versa (i.e., “transformed”).

Compared to a fixed-width encoding like UCS-2, a variable-width character encoding can employ a variable number of code units to encode each character. This bypasses the “one code unit per character” limitation of fixed-width encodings, and allows the representation of a much larger number of characters—potentially, an infinite number, depending on how many “lead units” are reserved as markers for multi-unit sequences.

Excluding the dead-on-arrival UTF-1, there are 4 UTF encodings in use today:

- UTF-8, a variable-width encoding that uses 1-byte characters

- UTF-16, a variable-width encoding that uses 2-byte characters

- UTF-32, a variable-width encoding that uses 4-byte characters

- UTF-EBCDIC, a variable-width encoding that uses 1-byte characters designed for IBM’s EBCDIC systems (note: I think it’s safe to argue that using EBCDIC in 2023 edges very close to being a felony)

UTF-16

To salvage the consistent investments made to support UCS-2, the Unicode Consortium created UTF-16 as a backward-compatible extension of UCS-2. When some piece of software advertises “support for UNICODE”, it almost always means that some software supported UCS-2 and switched to UTF-16 sometimes later. 6

Like UCS-2, UTF-16 can represent the entirety of the BMP using a single 16-bit value. Every codepoint above U+FFFF is represented using a pair of 16-bit values, called surrogate pairs. The first value (the “high surrogate”) is always a value in the range U+D800 to U+DBFF, while the second value (the “low surrogate”) is always a value in the range U+DC00 to U+DFFF.

This, in practice, means that the range reserved for BMP characters never overlaps with surrogates, making it trivial to distinguish between a single 16-bit codepoint and a surrogate pair, which makes UTF-16 self-synchronizing over 16-bit values.

Emojis are an example of characters that lie outside of the BMP; as such, they are always represented using surrogate pairs.

For instance, the character U+1F600 (😀) is represented in UTF-16 by the surrogate pair [0xD83D, 0xDE00]:

>>> # pack the surrogate pair into bytes by hand, and then decode it as UTF-16

>>> bys = [b for cp in (0xD83D, 0xDE00) for b in list(cp.to_bytes(2,'little'))]

>>> bys

[61, 216, 0, 222]

>>> bytes(bys).decode('utf-16le')

'😀'

The BOM

Notice that in the example above I had to specify an endianness for the bytes (little-endian in this case) by writing "utf-16le" instead of just "utf-16". This is due to the fact that UTF-16 is actually two different (incompatible) encodings, UTF-16LE and UTF-16BE, which differ in the endianness of the single codepoints. 7

The standard calls for UTF-16 streams to start with a Byte Order Mark (BOM), represented by the special codepoint U+FEFF. Reading 0xFEFF indicates that the endianness of a text block is the same as the endianness of the decoding system; reading those bytes flipped, as 0xFFFE, indicates opposite endianness instead.

As an example, let’s assume a big-endian system has generated the sequence [0xFE, 0xFF, 0x00, 0x61].

All systems, LE or BE, will detect that the first two bytes are a surrogate pair, and read them as they are depending on their endianness. Then:

- A big-endian system will decode

U+FEFF, which is the BOM, and thus will assume the text is in UTF-16 in its same byte endianness (BE); - A little-endian system will instead read

U+FFFE, which is still the BOM but flipped, so it will assume the text is in the opposite endianness (BE in the case of an LE system).

In both cases, the BOM allows the following character to be correctly parsed as U+0061 (a.k.a. a).

If no BOM is detected, then most decoders will do as they please (despite the standard recommending to assume UTF-16BE), which most of the time means assuming the endianness of the system:

>> import sys

>>> sys.byteorder

'little'

>>> # BOM read as 0xFEFF and system is LE -> will assume UTF-16LE

>>> bytes([0xFF, 0xFE, 0x61, 0x00, 0x62, 0x00, 0x63, 0x00]).decode('utf-16')

'abc'

>>> # BOM read as 0xFFFE and system is LE -> will assume UTF-16BE

>>> bytes([0xFE, 0xFF, 0x00, 0x61, 0x00, 0x62, 0x00, 0x63]).decode('utf-16')

'abc'

>>> # no BOM, text is BE and system is LE -> will assume UTF-16LE and read garbage

>>> bytes([0x00, 0x61, 0x00, 0x62, 0x00, 0x63]).decode('utf-16')

'愀戀挀'

>>> # no BOM, text is BE and UTF-16BE is explicitly specified -> will read the text correctly

>>> bytes([0x00, 0x61, 0x00, 0x62, 0x00, 0x63]).decode('utf-16be')

'abc'

Some decoders may probe the first few codepoints for zeroes to detect the endianness of the stream, which is in general not an amazing idea. As a rule of thumb, UTF-16 text should never rely on automated endianness detection, and thus either always start with a BOM or assume a fixed endianness value (which in the vast majority of cases is UTF-16LE, which is what Windows does).

UTF-32

Just as UTF-16 is an extension of UCS-2, UTF-32 is an evolution of UCS-4. Compared to all other UTF encodings, UTF-32 is by far the simplest, because like its predecessor, it is a fixed-width encoding.

The major difference between UCS-4 and UTF-32 is that the latter has been limited down 21 bits, from its maximum of 31 bits (UCS-4 was signed). This has been done to maintain compatibility with UTF-16, which is constrained by its design to only represent codepoints up to U+10FFFF.

While UTF-32 seems convenient at first, it is not in practice all that useful, for quite a few reasons:

-

UTF-32 is outrageously wasteful because all characters, including those belonging to the ASCII plane, are represented using 4 bytes. Given that the vast majority of text uses ASCII characters for markup, content or both, UTF-32 encoded text tends to be mostly comprised of just a few significant bytes scattered in between a sea of zeroes:

>>> # UTF-32BE encoded text with BOM >>> bytes([0x00, 0x00, 0xFE, 0xFF, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x61, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x62, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x63]).decode('utf-32') 'abc' >>> # The same, but in UTF-16BE >>> bytes([0xFE, 0xFF, 0x00, 0x61, 0x00, 0x62, 0x00, 0x63]).decode('utf-16') 'abc' >>> # The same, but in ASCII >>> bytes([0x61, 0x62, 0x63]).decode('ascii') 'abc' -

No major OS or software uses UTF-32 as its internal encoding as far as I’m aware of. While locales in modern UNIX systems usually define

wchar_tas representing UTF-32 codepoints, they are seldom used due to most software in existence assuming thatwchar_tis 16-bit wide.On Linux, for instance:

#include <locale.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <wchar.h> int main(void) { // one of the bajilion ways to set a Unicode locale - we'll talk UTF-8 later setlocale(LC_ALL, "en_US.UTF-8"); const wchar_t s[] = L"abc"; printf("sizeof(wchar_t) == %zu\n", sizeof *s); // 4 printf("wcslen(s) == %zu\n", wcslen(s)); // 3 printf("bytes in s == %zu\n", sizeof s); // 16 (12 + 4, due to the null terminator) return 0; } -

The fact UTF-32 is a fixed-width encoding is only marginally useful, due to grapheme clusters still being a thing. This means that the equivalence between codepoints and rendered glyphs is still not 1:1, just like in UCS-4:

// GNU/Linux, x86_64 #include <locale.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <wchar.h> int main(void) { setlocale(LC_ALL, "en_US.UTF-8"); // "caña", with 'ñ' written as the grapheme cluster "n" + "combining tilde" const wchar_t string[] = L"can\u0303a"; wprintf(L"`%ls`\n", string); // prints "caña" as 4 glyphs wprintf(L"`%ls` is %zu codepoints long\n", string, wcslen(string)); // 5 codepoints wprintf(L"`%ls` is %zu bytes long\n", string, sizeof string); // 24 bytes (5 UCS-4 codepoints + null) // this other string is the same as the previous one, but with the precomposed "ñ" character const wchar_t probe[] = L"ca\u00F1a"; const _Bool different = wcscmp(string, probe); // this will always print "different", because the two strings are not the same despite being identical wprintf(L"`%ls` and `%ls` are %s\n", string, probe, different ? "different" : "equal"); return 0; }$ cc -o widestr_test widestr_test.c -std=c11 $ ./widestr_test `caña` `caña` is 5 codepoints long `caña` is 24 bytes long `caña` and `caña` are differentThis is by far the biggest letdown about UTF-32: it is not the ultimate “extended ASCII” encoding most people wished for, because it is still incorrect so iterate over characters, and it still requires normalization (see below) in order to be safely operated on character by character.

UTF-8

I left UTF-8 as last because it is by far the best among the crop of Unicode encodings 8. UTF-8 is a variable width encoding, just like UTF-16, but with the crucial advantage that UTF-8 uses byte-sized (8-bit) code units, just like ASCII.

This is a major advantage, for a series of reasons:

- All ASCII text is valid UTF-8, and ASCII itself is in UTF-8, limited to the codepoints between

U+0000andU+007F.- This also implies that UTF-8 can encode ASCII text with one byte per character, even when mixed up with non-Latin characters;

- Editors, terminals and other software can just support UTF-8 without having to support a separate ASCII mode;

-

UTF-8 doesn’t require bothering with endianness, because bytes are just that - bytes. This means that UTF-8 does not require a BOM, even though poorly designed software may still add one (see below);

- UTF-8 doesn’t need a wide char type, like

wchar_torchar16_t. Old APIs can use classic byte-sizedchars, and just disregard characters aboveU+007F.

The following is an arguably poorly designed C program that parses a basic key-value file format defined as follows:

key1:value1

key2:value2

key\:3:value3

#include <stddef.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#define BUFFER_SIZE 1024

int main(const int argc, const char* const argv[]) {

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "usage: %s <file>\n", argv[0]);

return EXIT_FAILURE;

}

FILE* const file = fopen(argv[1], "r");

if (!file) {

fprintf(stderr, "error: could not open file `%s`\n", argv[1]);

return EXIT_FAILURE;

}

int retval = EXIT_SUCCESS;

char* line = malloc(BUFFER_SIZE);

if (!line) {

fprintf(stderr, "error: could not allocate memory\n");

goto end;

}

size_t line_size = BUFFER_SIZE;

ptrdiff_t key_offs = -1, pos = 0;

_Bool escape = 0;

for (;;) {

const int c = fgetc(file);

switch (c) {

case EOF:

goto end;

case '\\':

if (!escape) {

escape = 1;

continue;

}

break;

case ':':

if (!escape) {

if (key_offs >= 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "error: extra `:` at position %td\n", pos);

goto end;

}

key_offs = pos;

continue;

}

break;

case '\n':

if (escape) {

break;

}

if (key_offs < 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "error: missing `:`\n");

goto end;

}

printf("key: `%.*s`, value: `%.*s`\n", (int)key_offs, line, (int)(pos - key_offs), line + key_offs);

key_offs = -1;

pos = 0;

continue;

}

if ((size_t) pos >= line_size) {

line_size = line_size * 3 / 2;

line = realloc(line, line_size);

if (!line) {

fprintf(stderr, "error: could not allocate memory\n");

goto end;

}

}

line[pos++] = c;

escape = 0;

}

end:

free(line);

fclose(file);

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

$ cc -o kv kv.c -std=c11

$ cat kv_test.txt

key1:value1

key2:value2

key\:3:value3

$ ./kv kv_test.txt

key: `key1`, value: `value1`

key: `key2`, value: `value2`

key: `key:3`, value: `value3`

This program operates on files char by char (or rather, int by int—that’s a long story), using whatever the “native” 8-bit (“narrow”) execution character set is to match for basic ASCII characters such as :, \ and \n.

The beauty of UTF-8 is that code that splits, searches, or synchronises using ASCII symbols9 will work fine as-is, with little to no modification, even with Unicode text.

Standard C character literals will still be valid Unicode codepoints, as long as the encoding of the source file is UTF-8. In the file above, ':' and other ASCII literals will fit in a char (int, really) as long as they are encoded as ASCII (: is U+003A).

Like UTF-16, UTF-8 is self-synchronizing: the code-splitting logic above will never match a UTF-8 codepoint in the middle, given that ASCII is reserved all of the codepoints between U+0000 and U+007F. The text can then be returned to the UTF-8 compliant system as it is, and the Unicode text will be correctly rendered.

$ cat kv_test_utf8.txt

tcp:127.0.0.1

Affet, affet:Yalvarıyorum

Why? 😒:blåbær

Spla\:too:3u33

$ ./kv kv_test_utf8.txt

key: `tcp`, value: `127.0.0.1`

key: `Affet, affet`, value: `Yalvarıyorum`

key: `Why? 😒`, value: `blåbær`

key: `Spla:too`, value: `3u33`

Unicode Normalization

As I previously mentioned, Unicode codepoints can be modified using combining characters, and the standard supports precomposed forms of some characters which have decomposed forms. The resulting glyphs are visually indistinguishable after being rendered, and there’s no limitation on using both forms alongside each other in the same text bit of text:

>>> import unicodedata

>>> s = 'Störfälle'

>>> len(s)

10

>>> [unicodedata.name(c) for c in s]

['LATIN CAPITAL LETTER S', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER T', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER O WITH DIAERESIS', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER R', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER F', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER A', 'COMBINING DIAERESIS', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER L', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER L', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER E']

>>> # getting the last 4 characters actually picks the last 3 glyphs, plus a combining character

>>> # sometimes the combining character may be mistakenly rendered over the `'` Python prints around the string

>>> s[-4:]

'̈lle'

>>> [unicodedata.name(c) for c in s[-4:]]

['COMBINING DIAERESIS', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER L', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER L', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER E']

This is a significant issue, given how character-centric our understanding of text is: users (and by extension, developers) expect to be able to count what they see as “letters”, in a way that is consistent with how they are printed, shown on screen or inputted in a text field.

Another headache is the fact Unicode also may define special forms for the same letter or group of letters, which are visibly different but understood by humans to be derived from the same symbol.

A very common example of this is the fi (U+FB01), fl (U+FB02), ff (U+FB00) and ffi (U+FB03) ligatures, which are ubiquitous in Latin text as a “more readable” form of the fi, fl and ffi digraphs. In general, users expect office, office and office to be treated and rendered similarly, because they all represent the same identical word, but not necessarily without any visual difference. 10

Canonical and Compatibility Equivalence

To solve this issue, Unicode defines two different types of equivalence between codepoints (or sequences thereof):

-

Canonical equivalence, when two combinations of one or more codepoints represent the same “abstract” character, like in the case of “ñ” and “n + combining tilde”;

-

Compatibility equivalence, when two combinations of one or more codepoints more or less represent the same “abstract” character, while being rendered differently or having different semantics, like in the case of “fi”, or mathematical signs such as “Mathematical Bold Capital A” (

𝐀).

Canonical equivalence is generally considered a stronger form of equivalence than compatibility equivalence: it is critical for text processing tools to be able to treat canonically equivalent characters as the same, otherwise, users may be unable to search, edit or operate on text properly.11 On the other end, users are aware of compatibility-equivalent characters due to their different semantic and visual features, so their equivalence becomes relevant only in specific circumstances (like textual search, for instance, or when the user tries to copy “fancy” characters from Word to a text box that only accepts plain text).

Normalization Forms

Unicode defines four distinct normalization forms, which are specific forms a Unicode text can be in, and which allow for safe comparisons between strings. The standard describes how text can be transformed into any form, following a specific normalization algorithm based on per-glyph mappings.

The four normalization forms are:

-

NFD, or Normalization Form D, which applies a single canonical decomposition to all characters of a string. In general, this can be assumed to mean that every character that has a canonically-equivalent decomposed form is in it, with all of its modifiers sorted into a canonical order.

For instance,

>>> "e\u0302\u0323" 'ệ' >>> [unicodedata.name(c) for c in "e\u0302\u0323"] ['LATIN SMALL LETTER E', 'COMBINING CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT', 'COMBINING DOT BELOW'] >>> normalized = unicodedata.normalize('NFD', "e\u0302\u0323") >>> normalized 'ệ' >>> [unicodedata.name(c) for c in normalized] ['LATIN SMALL LETTER E', 'COMBINING DOT BELOW', 'COMBINING CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT']Notice how the circumflex and the dot below were in a noncanonical order and were swapped by the normalization algorithm.

-

NFC, or Normalization Form C, which first applies a canonical decomposition, followed by a canonical composition. In NFC, all characters are composed into a precomposed character, if possible:

>>> precomposed = unicodedata.normalize('NFC', "e\u0302\u0323") >>> precomposed 'ệ' >>> [unicodedata.name(c) for c in precomposed] ['LATIN SMALL LETTER E WITH CIRCUMFLEX AND DOT BELOW']Notice that normalizing to NFC is not enough to “count” glyphs, given that some may not be representable with a single codepoint. An example of this is

ẹ̄, which has no associated precomposed character:>>> [unicodedata.name(c) for c in unicodedata.normalize('NFC', "ẹ̄")] ['LATIN SMALL LETTER E WITH DOT BELOW', 'COMBINING MACRON']A particularly nice property of NFC is that by definition all ASCII text is by definition already in NFC, which means that compilers and other tools do not necessarily have to bother with normalization when dealing with source code or scripts. 12

-

NFKD, or Normalization Form KD, which applies a compatibility decomposition to all characters of a string. Alongside canonical equivalence, Unicode also defines compatibility-equivalent decompositions for certain characters, like the previously mentioned

filigature, which is decomposed intofandi.>>> fi = "fi" >>> unicodedata.name(fi) 'LATIN SMALL LIGATURE FI' >>> unicodedata.name(unicodedata.normalize('NFD', fi)) # doesn't do anything, `fi` has no canonical decomposition 'LATIN SMALL LIGATURE FI' >>> decomposed = unicodedata.normalize('NFKD', "fi") >>> decomposed 'fi' >>> [unicodedata.name(c) for c in decomposed] ['LATIN SMALL LETTER F', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER I']Characters that don’t have a compatibility decomposition are canonically decomposed instead:

>>> "\u1EC7" 'ệ' >>> [unicodedata.name(c) for c in unicodedata.normalize('NFKD', "\u1EC7") ['LATIN SMALL LETTER E', 'COMBINING DOT BELOW', 'COMBINING CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT'] -

NFKC, or Normalization Form KC, which first applies a compatibility decomposition, followed by a canonical composition. In NFKC, all characters are composed into a precomposed character, if possible:

>>> precomposed = unicodedata.normalize('NFKC', "fi") # this is U+FB01, "LATIN SMALL LIGATURE FI" >>> precomposed 'fi' >>> [unicodedata.name(c) for c in precomposed] ['LATIN SMALL LETTER F', 'LATIN SMALL LETTER I']Notice how the composition performed is canonical: there’s no such thing as “compatibility composition” as far as my understanding goes. This means that NFKC never recombines characters into compatibility-equivalent forms, which are thus permanently lost:

>>> s = "Souffl\u0065\u0301" # notice the `ff` ligature >>> s 'Soufflé' >>> norm = unicodedata.normalize('NFKC', s) >>> norm 'Soufflé' >>> # the ligature is gone, but the accent is still there

All in all, normalization is a fairly complex topic, and it’s especially tricky to implement right due to the sheer amount of special cases, so it’s always best to rely on libraries in order to get it right.

Unicode in the wild: caveats

Unicode is really the only relevant character set in existence, with UTF-8 holding the status of “best encoding”.

Unfortunately, internationalization support introduces a great deal of complexity into text handling, something that developers are often unaware of:

-

First and foremost, there’s still a massive amount of software that doesn’t default to (or outright does not support) UTF-8, because it was either designed to work with legacy 8-bit encodings (like ISO-8859-1) or because it was designed in the ’90s to use UCS-2 and it’s permanently stuck with it or with faux “UTF-16”. Software libraries and frameworks like Qt, Java, Unreal Engine and the Win32 API are constantly converting text from UTF-8 (which is the sole Internet standard) to their internal UTF-16 representation. This is a massive waste of CPU cycles, which while more abundant than in the past, are still a finite resource.

// Linux x86_64, Qt 6.5.1. Encoding is `en_US.UTF-8`. #include <iostream> #include <QCoreApplication> #include <QDebug> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { QCoreApplication app{argc, argv}; // converts UTF-8 (the source file's encoding) to the internal QString representation const QString s{"caña"}; // prints `"caña"``, using Qt's debugging facilities. This will convert back to UTF-8 in order // to print the string to the console qDebug() << s; // prints `caña`, using C++'s IOStreams. This will force Qt to convert the string to // a UTF-8 encoded std::string, which will then be printed to the console std::cout << s.toStdString() << '\n'; return 0; } -

Case insensitivity in Unicode is a massive headache. First and foremost, the concept itself of “ignoring case” is deeply European-centric due to it being chiefly limited to bicameral scripts such as Latin, Cyrillic or Greek. What is considered the opposite case of a letter may vary as well, depending on the system’s locale:

public class Up { public static void main(final String[] args) { final var uc = "CIAO"; final var lc = "ciao"; System.out.println(uc.toLowerCase()); System.out.println(lc.toUpperCase()); System.out.printf("uc(\"%s\") == \"%s\": %b\n", lc, uc, lc.toUpperCase().equals(uc)); } }$ echo $LANG en_US.UTF-8 $ java Up ciao CIAO uc("ciao") == "CIAO": trueThis seems working fine until the runtime locale is switched to Turkish:

$ env LANG='tr_TR.UTF-8' java Up cıao CİAO uc("ciao") == "CIAO": falseIn Turkish, the uppercase of

iisİ, and the lowercase ofIisı, which breaks the ASCII-centric assumption the Java13 snippet above is built on. There is a multitude of such examples of “naive” implementations of case insensitivity in Unicode that inevitably end up being incorrect under unforeseen circumstances.Taking all edge cases related to Unicode case folding into account is a lot of work, especially since it’s very hard to properly test all possible locales. This is the reason why Unicode handling is always best left to a library. For C/C++ and Java, the Unicode Consortium itself provides a reference implementation of the Unicode algorithms, called ICU, which is used by a large number of frameworks and shipped by almost every major OS.

While quite tricky to get right at times and at times more UTF-16 centric than I’d like, using ICU is still way saner than any self-written alternative:

#include <stdint.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <string.h> #include <unicode/ucasemap.h> #include <unicode/utypes.h> int main(const int argc, const char *const argv[]) { // Support custom locales const char* const locale = argc > 1 ? argv[1] : "en_US"; UErrorCode status = U_ZERO_ERROR; // Create a UCaseMap object for case folding UCaseMap* const caseMap = ucasemap_open(locale, 0, &status); if (U_FAILURE(status)) { printf("Error creating UCaseMap: %s\n", u_errorName(status)); return EXIT_FAILURE; } // Case fold the input string using the default settings const char input[] = "CIAO"; char lc[100]; const int32_t lcLength = ucasemap_utf8ToLower(caseMap, lc, sizeof lc, input, sizeof input, &status); if (U_FAILURE(status)) { printf("Error performing case folding: %s\n", u_errorName(status)); return 1; } // Print the lower case string printf("lc(\"%s\") == %.*s\n", input, lcLength, lc); // Clean up resources ucasemap_close(caseMap); return EXIT_SUCCESS; }$ cc -o casefold casefold.c -std=c11 $(icu-config --ldflags) $ ./casefold lc("CIAO") == ciao $ ./casefold tr_TR lc("CIAO") == cıaoUnicode generalises “case insensitivity” into the broader concept of character folding, which boils down to a set of rules that define how characters can be transformed into other characters, in order to make them comparable.

-

Similarly to folding, sorting text in a well-defined order (for instance alphabetical), an operation better known as collation, is also not trivial with Unicode.

Different languages (and thus locales) may have different sorting rules, even with the Latin scripts.

If, perchance, someone wanted to sort the list of words

[ "tuck", "löwe", "luck", "zebra"]:- In German, ‘Ö’ is placed between ‘O’ and ‘P’, and the rest of the alphabet follows the same order as in English. The correct sorting for that list is thus

[ "löwe", "luck", "tuck", "zebra"]; - In Estonian, ‘Z’ is placed between ‘S’ and ‘T’, and ‘Ö’ is the penultimate letter of the alphabet. The list is then sorted as

[ "luck", "löwe", "zebra", "tuck"]; - In Swedish, ‘Ö’ is the last letter of the alphabet, with the classical Latin letters in their usual order. The list is thus

[ "luck", "löwe", "tuck", "zebra"].

Unicode defines a complex set of rules for collation and provides a reference implementation in ICU through the

ucolAPI (and its relative C++ and Java equivalents).#define _GNU_SOURCE // for qsort_r #include <stdint.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <string.h> #include <unicode/ustring.h> #include <unicode/ucol.h> #include <unicode/uloc.h> int strcmp_helper(const void *const a, const void *const b, void *const ctx) { const char *const str1 = *(const char**) a, *const str2 = *(const char**) b; UErrorCode status = U_ZERO_ERROR; const UCollationResult cres = ucol_strcollUTF8(ctx, str1, strlen(str1), str2, strlen(str2), &status); return (cres == UCOL_GREATER) - (cres == UCOL_LESS); } void sort_strings(UCollator *const collator, const char **const strings, const ptrdiff_t n) { qsort_r(strings, n, sizeof *strings, strcmp_helper, collator); } int main(const int argc, const char *argv[]) { // Support custom locales const char* locale = getenv("ICU_LOCALE"); if (!locale) { locale = "en_US"; } UErrorCode status = U_ZERO_ERROR; // Create a UCaseMap object for case folding UCollator *const coll = ucol_open(locale, &status); if (U_FAILURE(status)) { printf("Error creating UCollator: %s\n", u_errorName(status)); return EXIT_FAILURE; } sort_strings(coll, ++argv, argc - 1); // Clean up resources ucol_close(coll); while (*argv) { puts(*argv++); } return EXIT_SUCCESS; }$ env ICU_LOCALE=de_DE ./coll "tuck" "löwe" "luck" "zebra" # German löwe luck tuck zebra $ env ICU_LOCALE=et_EE ./coll "tuck" "löwe" "luck" "zebra" # Estonian luck löwe zebra tuck $ env ICU_LOCALE=sv_SE ./coll "tuck" "löwe" "luck" "zebra" # Swedish luck löwe tuck zebra $ # more complex case: sorting Japanese Kana using the Japanese locale's gojūon order $ env ICU_LOCALE=ja ./coll "パンダ" "ありがとう" "パソコン" "さよなら" "カード" ありがとう カード さよなら パソコン パンダ - In German, ‘Ö’ is placed between ‘O’ and ‘P’, and the rest of the alphabet follows the same order as in English. The correct sorting for that list is thus

-

To facilitate UTF-8 detection when other encodings may be in use, some platforms annoyingly add a UTF-8 BOM (

EF BB BF) at the beginning of text files. Microsoft’s Visual Studio is historically a major offender in this regard:$ file OldProject.sln OldProject.sln: Unicode text, UTF-8 (with BOM) text, with CRLF line terminators $ xxd OldProject.sln | head -n 1 00000000: efbb bf0d 0a4d 6963 726f 736f 6674 2056 .....Microsoft VThe sequence is simply

U+FEFF, just like in UTF-16 and 32, but encoded in UTF-8. While it’s not forbidden by the standard per se, it has no real utility besides signaling that the file is in UTF-8 (it makes no sense talking about endianness with single bytes). Programs that need to parse or operate on UTF-8 encoded files should always be aware that a BOM may be present, and probe for it to avoid exposing users to unnecessary complexity they probably don’t care about. -

Because of all of the reasons listed above, random, array-like access to Unicode strings is almost always broken—this is true even with UTF-32, due to grapheme clusters. It also follows that operations such as string slicing are not trivial to implement correctly, and the way languages such as Python and JavaScript do it (codepoint by codepoint) is IMHO arguably problematic.

A good example of a modern language that attempts to mitigate this issue is Rust, which has UTF-8 strings that disallow indexed access and only support slicing at byte indices, with UTF-8 validation at runtime:

fn main() { let s = "caña"; // error[E0277]: the type `str` cannot be indexed by `{integer}` // let c = s[1]; // char-by-char access requires iterators println!("{}", s.chars().nth(2).unwrap()); // OK: ñ // this will crash the program at runtime: // "byte index 3 is not a char boundary; it is inside 'ñ' (bytes 2..4) of `caña`" // let slice = &s[1..3]); // the user needs to check UTF-8 character bounds beforehand println!("{}", &s[1..4]); // OK: "añ" }The stabilisation of the

.chars()method took quite a long time, reflecting the fact that deducing what is or is not a character in Unicode is complex and quite controversial. The method itself ended up implementing iteration over Rust’schars (aka, Unicode scalar codepoints) instead of grapheme clusters, which is rarely what the user wants. The fact it returns an iterator does at least effectively express that character-by-character access in Unicode is not, indeed, the “simple” operation developers have been so long accustomed to.

Wrapping up

Unicode is a massive standard, and it’s constantly adding new characters14, so for everybody’s safety it’s always best to rely on libraries to provide Unicode support, and if necessary ship fonts that support all the characters you may need (such as Noto Fonts). As previously introduced, C and C++ do not provide great support for Unicode, so it’s always best to just use ICU, which is widely supported and shipped by every major OS (including Windows).

When handling text that may contain non-English characters, it’s always best to stick to UTF-8 when possible and use Unicode-aware libraries for text processing. While writing custom text processing code may seem doable, it’s easy to miss a few corner cases and confuse end users in the process.

This is especially important because the main users of localized text and applications tend to often be the least technically savvy—those who may lack the ability to understand why the piece of software they are using is misbehaving, and can’t search for help in a language they don’t understand.

I hope this article may have been useful to shed some light on what is, in my opinion, an often overlooked topic in software development, especially among C++ users. If I had to be honest, I was striving for a shorter article, but I guess I had to make up for all those years I didn’t post a thing :)

As always, feel free to comment underneath or send me a message if anything does not look right, and hopefully, the next post will come before 2025…

-

This wacky yet ingenious system made it possible to write in Arabic on ASCII-only channels, by using a mixture of Latin script and Western numerals with a passing resemblance with letters not present in English (i.e.,

3in place ofع, …). ↩ -

Three actually: there was also UTF-1, a variable-width encoding that used 1 byte characters. It was pretty borked, so it never really saw much use. ↩

-

32-bit Unicode was initially resisted by both the Unicode consortium and the industry, due to its wastefulness while representing Latin text and everybody’s heavy investment in 16-bit Unicode. ↩

-

And they still do it as of today. They do claim UTF-16 support, but it’s a bald-faced lie given that they don’t support anything outside of the BMP. ↩

-

It was basically IPv4 all over again. I guess we’ll never learn. ↩

-

A good example of this is Unreal Engine, which pretends to support UTF-16 even though it is actually UCS-2 ↩

-

UCS-2 also had the same issue, and so it was also in practice two different encodings, UCS-2LE and UCS-2BE. My opinions on this matter can thankfully be represented using Unicode itself with codepoint

U+1F92E. ↩ -

Or rather, it is the one Unicode encoding people want to use, as opposed to UTF-16, which is a scourge we’ll (probably) never get rid of. ↩

-

I’ve specified “ASCII symbols” because letters may potentially be part of a grapheme cluster, so splitting on an

emay, for instance, split anéin two. ↩ -

For instance, you most definitely expect that searching for “office” in a PDF also matches the words containing the ligature “fi”—string search is another tricky topic by itself. ↩

-

And not only that: just think of how hard would it be to find a file, or to check a password or username, if there weren’t ways to verify the canonical equivalence between characters. ↩

-

While most programming languages are somewhat standardizing around UTF-8 encoded source code, C and C++ still don’t have a standard encoding. Modern languages like Rust, Swift and Go also support Unicode in identifiers, which introduces some interesting challenges - see the relative Unicode specification for identifiers and parsing for more details. ↩

-

I’ve used Java as an example here because it hits the right spot as a poster child of all the wrong assumptions of the ’90s: it’s old enough to easily provide naive, Western-centric built-in concepts such as “toUpperCase” and “toLowerCase”, while also attempting to implement them in a “Unicode” way. Unicode support in C and C++ is too barebones to really work as an example (despite C and C++ locales being outstandingly broken), and modern ones such as Rust or Go are usually locale agnostic; they also tend to implement case folding in a “saner” way (for instance, Rust only supports it on ASCII in its standard library). ↩

-

A prime example of this is emojis, which have been ballooning in number since they were first introduced in 2010. ↩